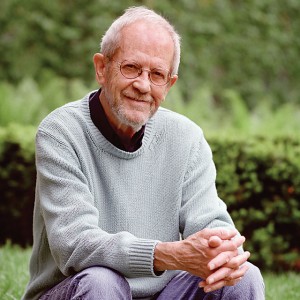

Elmore Leonard (Get Shorty, Justified) said:

“All the information you need can be given in dialogue.”

He’s on to something. I can’t tell you how quickly poor dialogue ruins a novel for me. The sad thing is I have started a book before where the “telling” starts off very, very well. I am intrigued. I am impressed. And then, the first line of dialogue. It’s not unlike smelling a wonderful dish as it is prepared in the kitchen and imagining how delectable it will taste, then seeing the dish as it is delivered, and ogling over the brilliant presentation, your saliva glands going stepping up to double-time–then raising a bite to your mouth, delicately placing it on your tongue, and tasting a flavor so horrific the only response is to spit it right out on the tablecloth, Miss Manners be damned.

Here’s a twist on Leonard’s wise maxim:

“Bad dialogue can erase any measure of good storytelling.”

That’s mine; you can feel free to quote me.

Writing dialogue is an art form within the art form. I know a lot of readers who will many times end up scanning to the dialogue. Let’s face it, most 100,000 word novels could very likely subsist (and even improve) at 50,000 words. As a writer, I have come to love words, but even I will begin scanning through weak prose; I’ll even do it in a well-written book, if there are too many examples of what Thomas Jefferson called “using two words where one will do.” I’m guessing most of us have done that. But it’s far rarer for a reader to skip dialogue. Dialogue is the savory meat behind the gorgeous, roasted russet potatoes.

In fact, great dialogue can rescue mediocre writing.

To further illustrate Leonard’s point, I was once tasked in a creative writing course with penning an entire short story with dialogue only. The writer was allowed one paragraph of a few sentences at the beginning to create the setting. An introduction only; no more than two to three sentences of basic information to lay the canvas. Then, a thousand to fifteen hundred words of dialogue.

It was a blast, and one of the most visceral, helpful exercises I have ever completed. You want to learn how to write dialogue that tells a story, try writing one in dialogue only. You’ll either learn the trade and have a story at the end, or you won’t, and all you’ll have is empty dialogue.

Here are a few other suggestions to assist in the writing of your crucial dialogue:

Speak plainly and don’t overcomplicate.

Speak plainly and don’t overcomplicate.

You’ll be tempted to try your hand at regional dialect, character-specific colloquialisms and affectations, and other character complexities. If you are convinced you must, you had better have one heck of an ear (and I’ve known few writers who could write a dialect successfully without having been around it so extensively as to have really picked up the nuances—even when that is the case, it can be very difficult to write it). The truth is, most readers aren’t going to know the dialect anyway, so unless it is done well enough to enhance the experience (i.e. have the reader literally learning an interesting affectation), it’s almost a no-win scenario. Even if you do it well, it may not make much difference—however, the downside is huge.

Pay attention to tempo, rhythm, and cadence.

This is a good rule of thumb for your storytelling in general. The best example of dialogue cadence is Good Joke versus Bad Joke. At least half of the success or failure of a joke is in the telling. Ask any comedian. We’ve all known them, funny people who could elicit a laugh reading back your grocery list. Timing is everything in storytelling, and no more so than in dialogue.

Try for normal speech patterns, stanzas, stops, and starts. A simple example:

“I went down to the basement and found him dead.”

“I found him in the basement. He was dead.”

There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with the first piece of dialogue. But ask yourself: is that how you would say it? Too often writers choose not to differentiate between their descriptive voice and their dialogue. People don’t speak as writers write. They use shortcuts. They shorten their sentences. They end with propositions. Which leads to the next suggestion:

Lighten up on the grammar rules.

This does NOT mean a free-for-all. It’s not a license to kill. However, when we speak, we pay less attention to grammar, otherwise we sound stiff, stuffy, and sterile. We use contractions. We pause for effect. We drift off…

We do a lot of things we wouldn’t do in writing. It can be a fine line. But in general, you can add a little authenticity to your dialogue by loosening up a bit. NOTE: You shouldn’t misspell, or use “your” for “you’re”…again, it can be a a fine line. You are still the writer of the dialogue. Any miscues that have nothing to do with how the character speaks are yours.

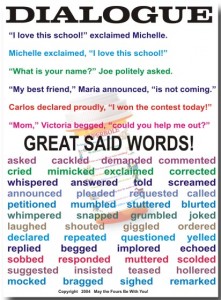

Sub-suggestion: Use said. A lot. Try to limit the words you use in place of it. Minimize your attempts to tell the reader what the character is saying. Let the dialogue SAY IT. You will be pleasantly surprised. Try it—go through a stretch of dialogue in your writing and use said (except where you eliminate it altogether—in spots where the back and forth conversation between two characters makes it obvious who is speaking, replying, etc.). Now read back through it, trying not to think too much about what you just did. The “saids” will become almost invisible. Which is what you want.

Need examples of words to avoid? See the pic on the left. You’ll be tempted to believe they are great substitutions for the boring old SAID. They aren’t. They are weak, weak, and more weak. Leonard has this to say in his book “Ten Rules of Writing”:

The line of dialogue belongs to the character; the verb is the writer sticking his nose in. But said is far less intrusive than grumbled, gasped, cautioned, lied.

You can also likely drop 90+% of the modifiers you couldn’t resist slopping in there:

She said exasperatingly.

He told her unconditionally.

Trust me, if you load your dialogue with modifiers, you are done like dinner.

Exasperatingly so.

Unconditionally.

In the end, there is only one way to acquire a “good ear” for dialogue:

In the end, there is only one way to acquire a “good ear” for dialogue:

Listen. Pay attention to the way people speak. Imitate them. Be a parrot. Speak your dialogue lines out loud and see if they spread the mustard.

The last suggestion: Don’t underestimate the power of your dialogue. Work on it. Like the golfer working on the short game, know that it can likely never reach perfection, yet requires constant diligence to make it even worthwhile.

Oh, and enjoy writing it. These are the moments when your characters are allowed to talk back.

Even to YOU.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The blank page is dead…long live the blank page.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I really enjoyed this post, its true to say that we can all be a bit stuffy at times with our writing, as we are concentrating on perfection in every way, however sometimes to loosen up just a little makes complete sense! There are some very insightful and useful suggestions here today which I have taken away with me. Thank you for a wonderful post.

[…] Say It, Don’t Spray It. (And Don’t Tell It.) […]

[…] A fabulous article on writing dialogue: Say It, Don’t Spray It. […]